Howard Zinn, Intellectual Moron

by Daniel J. Flynn“Objectivity is impossible,” self-styled “peoples’ historian” Howard Zinn once remarked, “and it is also undesirable. That is, if it were possible it would be undesirable, because if you have any kind of a social aim, if you think history should serve society in some way; should serve the progress of the human race; should serve justice in some way, then it requires that you make your selection on the basis of what you think will advance causes of humanity.”

History serving “a social aim,” rather than chronicling the past in a detached manner, is what readers get in A People’s History of the United States. With any luck, “The People Speak,” the History Channel documentary based on the book that premieres this Sunday, will be, like so many Hollywood productions, unfaithful to the original. Given A People’s History of the United States’ infidelity to facts, this might be the only chance viewers have of seeing anything resembling an accurate retelling of history.

Through Zinn’s looking-glass, Maoist China, site of history’s bloodiest state-sponsored killings, transforms into “the closest thing, in the long history of that ancient country, to a people’s government, independent of outside control.” The authoritarian Nicaraguan Sandinistas were “welcomed” by their own people, while the opposition Contras, who backed the candidate that triumphed when free elections were finally held, were a “terrorist group” that “seemed to have no popular support inside Nicaragua.” Admitting some human rights abuses, Zinn writes that Castro’s Cuba “had no bloody record of suppression.”

Readers of A People’s History of the United States learn very little about history. They learn quite a bit about Howard Zinn. In fact, the book is perhaps best thought of as a massive Rorschach Test, with the author’s familiar reaction to every major event in American history proving that his is a captive mind long closed by ideology.

If you’ve read Karl Marx, there’s no reason to read Howard Zinn. In fact, reading the most important line of The Communist Manifesto makes a study of A People’s History of the United States a colossal waste of time. The single-bullet theory of history offered by Marx–“The history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggle”–is relied upon by Zinn to explain all of American history. Economics determines everything. Why study history when theory has all the answers?

Thumb through A People’s History of the United States and one finds greed motivating every major event. According to Zinn, the separation from Great Britain, the Civil War, and both world wars—to name but a few examples—all stem from base motives involving rich men seeking to get richer at the expense of other men.

Zinn’s projection of Marxist theory upon historical reality begins with Columbus. According to Zinn, those following the seafaring Italian to the New World did so for one reason: profit. “Behind the English invasion of North America, behind their massacre of Indians, their deception, their brutality, was that special powerful drive born in civilizations based on private property,” maintains the octogenarian scribe.

A materialist interpretation continues with the Founding. “Around 1776,” A People’s History informs, “certain important people in the English colonies made a discovery that would prove enormously useful for the next two hundred years. They found that by creating a nation, a symbol, a legal unity called the United States, they could take over land, profits, and political power from the favorites of the British Empire. In the process, they could hold back a number of potential rebellions and create a consensus of popular support for the rule of a new, privileged leadership.”

Zinn sarcastically adds, “When we look at the American Revolution this way, it was a work of genius, and the Founding Fathers deserve the awed tribute they have received over the centuries. They created the most effective system of national control devised in modern times, and showed future generations of leaders the advantages of combining paternalism with command.” Rather than the spark that lit the fire of freedom and self-government throughout much of the world, he portrays the American Founding as a diabolically creative way to ensure oppression. If the Founders wanted a society they could direct, why didn’t they put forth a dictatorship or a monarchy resembling most other governments at the time? Why go through the trouble of devising a constitution guaranteeing rights, political participation, jury trials, and checks on power? Zinn doesn’t explain, contending that these freedoms and rights are merely a facade designed to prevent class revolution.

Zinn paints antebellum America as a uniquely cruel slaveholding society subjugating man for profit. Curiously, the war that ultimately results in slavery’s demise is portrayed as a conflict of oppression too. Zinn writes, “it is money and profit, not the movement against slavery, that was uppermost in the priorities of the men who ran the country.” Rather than welcoming emancipation, as one might expect, Zinn casts a cynical eye towards it. “Class consciousness was overwhelmed during the Civil War,” the author laments, placing a decidedly negative spin on the central event in American history. America is in a lose/lose situation. The same thing, according to Zinn, caused both slavery and emancipation: greed. Whether the U.S. tolerates or eradicates slavery, its nefarious motives remain the same. Zinn’s jaundiced eye fails to see the real issues surrounding the Civil War. Instead, he envisions the chief significance of the grisly conflict as how it allegedly served as a distraction from the impending socialist revolution.

By the time the reader reaches World War I, Zinn begins to sound like a broken record. “American capitalism needed international rivalry—and periodic war—to create an artificial community of interest between rich and poor,” the Boston University emeritus professor of history writes of the Great War, “supplanting the genuine community of interest among the poor that showed itself in sporadic movements.” Yet another diversion to delay the revolution!

“A People’s War?” is Zinn’s chapter on the war in which he served his country. Zinn suggests that America, not Japan, was to blame for Pearl Harbor by provoking the Empire of the Sun. The fight against fascism was all an illusion. While Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan may have been America’s enemies, Uncle Sam’s real goal was empire. Regarding America’s neutrality in the Spanish Civil War, Zinn asks: “[W]as it the logical policy of a government whose main interest was not stopping Fascism but advancing the imperial interests of the United States? For those interests, in the thirties, an anti-Soviet policy seemed best. Later, when Japan and Germany threatened U.S. world interests, a pro-Soviet, anti-Nazi policy became preferable.” Reality is inverted. It’s not the Soviet Union that went from being anti-Nazi to pro-Nazi to anti-Nazi. Zinn projects the Soviet Union’s schizophrenic policies upon the United States. While Zinn awkwardly excuses the Hitler-Stalin Pact, he all but proclaims a Hitler-Roosevelt Pact.

The reader learns that the Second World War was really about—surprise!—money. “Quietly, behind the headlines in battles and bombings,” Zinn writes, “American diplomats and businessmen worked hard to make sure that when the war ended, American economic power would be second to none in the world. United States business would penetrate areas that up to this time had been dominated by England. The Open Door Policy of equal access would be extended from Asia to Europe, meaning that the United States intended to push England aside and move in.” Yet, this didn’t happen. The English Empire expired, but no American Empire took its place. Despite defeating Japan and helping to vanquish Germany, America rebuilt these countries. They are now America’s chief economic rivals, not its colonies.

The profit motive certainly is central to numerous major events in American history. The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Fort in 1848, for example, undeniably stands as the primary reason—alongside the favorable outcome of the Mexican War—for the subsequent population explosion in California. The Gold Rush is one of several historical occurrences that conform to Zinn’s overall thesis. Even a broken clock is right twice a day. For every major figure or event whose catalyst was economic interests, scores were sparked by some unrelated concern.

To question Zinn’s method of analyses is not to say that economics does not influence events. It is to say that one-size-fits-all explanations of history are bound to be wrong more than they are right. History is too complicated to find a perfect fit within any theory. For the true believer, this inconvenience can be overcome. When fact and theory clash, ideologues choose theory. To the true believer, ideology is truth. Time and again, A People’s History of the United States opts to mold the facts to fit theory, leaving the reader to wonder what “people” he is referring to in the book’s title. Dishonest people? Left-wing people? Delusional people?

“Unemployment grew in the Reagan years,” Zinn claims. Statistics show otherwise. Reagan inherited an unemployment rate of 7.5 percent. By his last month in office, the rate had declined to 5.4 percent. Had the Reagan presidency ended in 1982 when unemployment rates exceeded 10 percent, Zinn would have a point. But for the remainder of Reagan’s presidency, unemployment declined precipitously. While Zinn teaches history and not mathematics, one needn’t be a math whiz to figure out that 5.4 percent is less than 7.5 percent. Despite unleashing an economy that created nearly 20 million new jobs during his tenure, Reagan continues to be smeared by historians—and it’s not hard to figure out why. Reagan’s free market polices were anathema to Marxists like Zinn. Upset at the pleasant way things turned out—Reagan’s policies unleashed an economy that continuously grew from late 1982 until mid 1990—historians prefer to rewrite history.

These are but a few of Zinn’s errors, which curiously seem to always bolster the left-of-center position. No error goes against the grain of the author’s general thesis. Every author makes mistakes. Zinn, it seems, would make less of them if he used his mind rather than his ideology to do his thinking.

By now one might be thinking: On what evidence does Zinn base his varied proclamations? One can only guess. Despite its scholarly pretensions, the book contains not a single source citation. While a student in Professor Zinn’s classes at Boston University or Spelman College might have received an “F” for turning in a paper without documentation, Zinn’s footnote-free book is standard reading in scores of college courses.

More striking than Zinn’s inaccuracies—intentional and otherwise—is what he leaves out.

Washington’s Farewell Address, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, and Reagan’s “tear down the wall” speech at the Brandenburg Gate all fail to merit a mention. Nowhere do we learn that Americans were first in flight, first to fly solo across the Atlantic, and first to walk on the moon. Alexander Graham Bell, Jonas Salk, and the Wright Brothers are entirely absent. Instead, the reader is treated to the exploits of Speckled Snake, Joan Baez, and the Berrigan brothers. While Zinn highlights immigrants that went into professions such as ditch-digging and prostitution, he excludes success stories like Alexander Hamilton, John Jacob Astor, and Louis B. Mayer. Valley Forge rates a single fleeting reference, while D-Day’s Normandy invasion, Gettysburg, and other important military battles are left out. In their place, we get several pages on the My Lai massacre and colorful descriptions of U.S. bombs falling on hotels, air-raid shelters, and markets during 1991’s Gulf War.

How do readers learn about U.S. history with all these omissions? They don’t.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

loading..

Featured Post

(no nuance to HillaryClinton's views) she made it clear in her recent book

IN THE MIDDLE EAST CHAPTER OF HER BOOK MS CLINTON MAKES STATEMENTS THAT AT BEST COULD BE CONSIDERED INSENSITIVE TO ISRAEL, OR AT WORST THA...

#CriticalAnalyst

-

▼

2009

(534)

-

▼

December

(144)

- $150,000 Settlement for Black Public School Studen...

- Gay Kosher Taharat hamishpachah

- no Jewish American Literature

- Howard Dean, Obama Officials and Dems Support Glob...

- Ford Motor Company Kept Workers Who Praised 9/11 E...

- Hariri is no Saint

- Is an Iranian intifada imminent?

- So Sad, Too Bad: Egypt Thwarts Anti-Israel Americ...

- http://xrl.us/Islamic drivers have a license to ki...

- Egypt claims Netanyahu willing to go back to armis...

- Gates of Vienna: More on Abdul Farouk Abdulmutallab

- Why Abbas Does Not Want To Resume Peace Talks - Hu...

- Iran: A Secret Deal for Purified Uranium from Kaza...

- Ron Ron Paul used the Occupation word on Larry Kin...

- Israel and the Arabs agree! Jimmy Carter didn't a...

- US slams new plans to build in east Jerusalem | Is...

- Twitter: Bring Back Noah David Simon!

- http://xrl.us/DhimmiNewYear CAIR: NY Muslims Featu...

- 2010 predictions: Another turbulent year ahead for...

- A Tale of Two Gazas: Website Pictures Deny ‘Humani...

- Eolake Stobblehouse thoughts: William Gibson on audio

- the Gold Bubble

- The Last Temptation of Ruth

- American Power: Mousavi Nephew Killed in Tehran Pr...

- What Obama could of learned from Nixon about Asian...

- a Leftist opinion on China - What is their side of...

- Was Brittany Murphy Jewish?

- Europe Wants to Divide Jerusalem - Hudson New York

- Good News for Jews for 2010

- Former Secret Service agent opens window into priv...

- the NYTimes now wants to BOMB Iran, but can they e...

- Lashon Ha-Ra לשון הרע

- Israel: The Political Collapse of Opposition Leade...

- Tariq Ali is Edward Said Jr

- Sara - Are you Going To Be My Girl?

- other apologies I'd like to see Carter make

- THE MYTH OF US PROFIT FROM IRAQI OIL

- Russia and Iran perpetuate the illusion of an alli...

- Israeli Scientists prove Marijuana is Good for Stress

- Carter: Grandson’s race not reason enough to apolo...

- Iran holding Osama bin Laden family members?

- Coasties, JAPs, Sexism, Weeds, Rejuveniles and the...

- Weasel Zippers: Senator Mary Landrieu On 'Louisian...

- 1920 The year the Arabs discovered Palestine

- Father of the Iranian revolution | Op-Ed Contribut...

- ObamaCare and Mom

- RandiZuckerberg loves Dubai and CNN

- Star Trek Naiveté

- Hariri is no Saint

- UK PRODUCT BOYCOTT

- Dems’ health bill passes key Senate vote - Health ...

- MK Tirosh: Uk boycott makes peace talks irrelevant...

- Ayalon Warns EU Over Jerusalem Decision - Politics...

- account gap is reducing supply of dollars overseas -

- National Journal Online - Obama Gets Low Marks On ...

- Jihad Watch Awards 2009: Nominations are now open!...

- Vulgar Americans

- before the Kyoto Protocols and Global Warming we h...

- U.S. cruise missile strike targets al-Qaeda in Yem...

- Rock The Vote: Stop Fucking People Who Are Opposed...

- Twitter hacked by Iranian Cyber Army; signs off wi...

- Democracy Broadcasting

- Stranded in Muslim holy city

- Copenhagen FAIL

- What Did You Do With Your Day?

- Sherry Dickson

- PageOneQ | Man to take polygraph to answer claims ...

- YouTube - Franken Denies Lieberman an 'Additio...

- Why doesn't FOX News have a competitor?

- Editorial - Twitter Tapping - NYTimes.com

- Big Hollywood » Blog Archive » Oliver Stone Scr...

- Chelsea Clinton is to marry Marc Mezvinsky

- Shiloh Musings: President sic Abbas: World Must R...

- DOWN WITH THE QUEEN!

- Global Warming: They Will Never Be Convinced

- Nay, I’ll have a starling

- don't poop where you eat

- Who is to blame? Tiger Woods or the mistresses

- Why are Americans so pro-Israel? :: Jeff Jacoby

- Code Pink

- Global Oil Firms Win Iraq Contracts - WSJ.com

- Palestinians alone again - Israel Opinion, Ynetnews

- Eye On The World: Peculiar news from Syria: Assad'...

- Alan Dershowitz on the Goldstone Report @ Fordham

- Doc's Talk: The Palestinians Tell the World Their ...

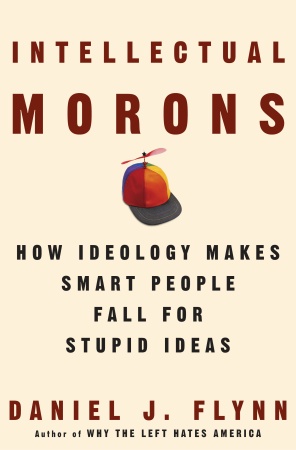

- Big Hollywood » Blog Archive » Howard Zinn, Int...

- Rush On Shatner's Raw Nerve

- Chanuka Robot

- Happy Chanukah from the Al Qaeda Dancers!

- KGB chief ordered Hitler's remains destroyed - DNA...

- If attacked, Iran wants Syria to hit back at Israe...

- NYTimes Reviews a book by David Priestland about C...

- Palinism - December 2, 2009 - The New York Sun

- The Volokh Conspiracy » Blog Archive » Israel’s...

- @Atlasshrugs @KristeeKelley talk about Sharia and ...

- Sarah Palin Is Coming to Town - Opinionator Blog -...

- Hoax and Change: Climategate Evidence ..... not Ha...

- Mathematically Correct Breakfast -- Mobius Sliced ...

- One Man’s Discarded Ticket Can Be Another Man’s Sa...

- Islamic Default

-

▼

December

(144)