US policy, “Keep up the good work!”

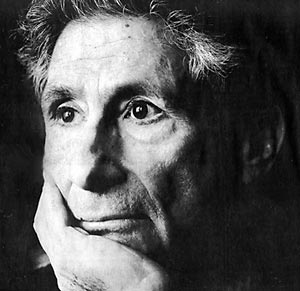

Michelle Obama and Barack Obama listen to Professor Edward Said

give the keynote address at an Arab community event in Chicago, May 1998.

(Photo: Ali Abunimah)...If disappointing, given his historically close relations to Palestinian-Americans, Obama’s about-face is not surprising. He is merely doing what he thinks is necessary to get elected and he will continue doing it as long as it keeps him in power. via electronicintifada.netwhat Americans Voted for is frightening. Obama’s hard-Left tilt is real.It’s time to revisit the issue of President Obama’s Palestinian ties. During his time in the Illinois state senate, Obama forged close alliances with the most prominent Palestinian political leaders in America. Substantial evidence also indicates that during his pre-Washington years, Obama was both supportive of the Palestinian cause and critical of America’s stance toward Israel. Although Obama began to voice undifferentiated support for Israel around 2004 (as he ran for U.S. Senate and his national visibility rose), critics and even some backers have long suspected that his pro-Palestinian inclinations survive.

The continuing influence of Obama’s pro-Palestinian sentiments is the best way to make sense of the president’s recent tilt away from Israel. This is why supporters of Israel should fear Obama’s reelection. In 2013, with his political vulnerability a thing of the past, Obama’s pro-Palestinian sympathies would be released from hibernation, leaving Israel without support from its indispensable American defender.

To see this, we need to reconstruct Obama’s pro-Palestinian past and assess its influence on the present. Taken in context, and followed through the years, the evidence strongly suggests that Obama’s long-held pro-Palestinian sentiments were sincere, while his post-2004 pro-Israel stance has been dictated by political necessity.

Let’s begin at the beginning — with the controversial question of whether Obama’s cultural heritage through his nominally Muslim Kenyan father and his Muslim Indonesian stepfather, along with his having been raised for a time in predominantly Muslim Indonesia, might have had some effect on the president’s mature foreign-policy views. Obama supporters often mock this idea, but we have it on high authority that Obama’s unusual heritage and upbringing have had an effect on his adult views.

Top presidential aide and longtime Obama family friend Valerie Jarrett was born and raised in Iran for the first five years of her life. In explaining how she first grew close to Obama, Jarrett says they traded stories of their youthful travels. As Jarrett told Obama biographer David Remnick: “He and I shared a view of where the United States fit in the world, which is often different from the view people have who have not traveled outside the United States as young children.” Remnick continues: “Through her travels, Jarrett felt that she had come to see the United States with a greater objectivity as one country among many, rather than as the center of all wisdom and experience.” Speaking with the authority of a close personal friend and top political adviser, then, Jarrett affirms that she and Obama reject traditional American exceptionalism. One hallmark of America’s exceptionalist perspective, of course, is our unique alliance with a democratic Israel, even in the face of intense criticism of that alliance from much of the rest of the world.

Obama’s close friend and longtime ally, Rashid Khalidi, Edward Said’s successor as the most prominent American advocate for the Palestinians, goes further. Khalidi told the Los Angeles Times that as president, Obama, “because of his unusual background, with family ties in Kenya and Indonesia, would be more understanding of the Palestinian experience than typical American politicians.” Khalidi’s testimony is important, since he speaks on the basis of years of friendship with Obama.

Edward Said - Orientalism

Center for 'Palestine' Studies

at Columbia University

AKA Bir Zeit on the Hudson

and taqiyyah

Those who know Obama best, then, affirm that his foreign-policy views are atypical for an American politician, and are grounded in his unique international heritage and upbringing. That is important, because our core task is to decide whether Obama’s pro-Palestinian past was a stance rooted in sincere sympathy, or nothing but a convenient sop to his leftist Hyde Park supporters. Jarrett and Khalidi give us reason to believe that Obama’s decidedly pro-Palestinian inclinations are rooted in his core conception of who he is.

Obama came to political consciousness at college, and prior to his discovery of community organizing late in his senior year, his focus was on international issues. Obama’s memoir, Dreams from My Father, highlights his anti-apartheid activism during his sophomore year at California’s Occidental College. Obama’s anti-apartheid stance, however, was part of a far broader and more radical rejection of the West’s alleged imperialism. Obama himself tells us, in a famous passage in Dreams, that he was taken with criticism of “neocolonialism” and “Eurocentrism” during these early college years.

What Obama doesn’t tell us, but what I reveal in Radical-in-Chief, my political biography of the president, is that he was a convinced Marxist during his college years. More important, once Obama graduated and entered the world of community organizing, he absorbed the sophisticated and intentionally stealthy socialism of his mentors. Obama’s socialist mentors strongly supported what they saw as the “liberation struggles” carried on by rebels against American “oppression” throughout the world. So Obama’s continuous radical political history strongly suggests that his early support for Palestine’s “liberation struggle” grew out of authentic political conviction, not pandering.

Although Obama has long withheld his college transcripts from the public, the Los Angeles Times reported in 2008 that Obama took a course from Edward Said sometime during his final two undergraduate years at Columbia University. This was just around the time Obama’s ties to organized socialism were deepening, and certainly suggests a sincere interest in Said’s radical views. As Martin Kramer points out, in his superb 2008 review of Obama’s Palestinian ties, Said had just then published his book The Question of Palestine, definitively setting the terms of the academic Left’s stance on the issue for decades to come.

After Obama finished his initial community-organizing stint in Chicago and graduated from Harvard Law School, he settled down to a teaching job at the University of Chicago around 1992, and went about laying the foundations of a political career. Sometime not long after his arrival at the University of Chicago, Obama connected with Rashid Khalidi.

To say the least, Rashid Khalidi is a controversial fellow. To begin with, although Khalidi denies it, Martin Kramer has unearthed powerful evidence suggesting that Khalidi was at one time an official spokesman for the Palestine Liberation Organization. Also, in the years immediately prior to his friendship with Obama, Khalidi was a leading opponent of the first Gulf War, which successfully reversed Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. According to Kramer, Khalidi condemned that action as an American “colonial war,” insisting that before we could end Saddam’s occupation of Kuwait, we would first have to end Israel’s supposedly equivalent occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. As Kramer puts it, Khalidi’s influence helped turn the University of Chicago of the Nineties into “the hot place to be for . . . trendy postcolonialist, blame-America, trash-Israel” scholarship.

While we don’t know exactly when their friendship began, Khalidi was reportedly present at the famous 1995 kickoff reception for Obama’s first political campaign, held at the home of Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn. That is no minor point. We’ll see that as Khalidi’s close friend and political ally, Ayers played an integral role in the story of Obama’s relationship with Khalidi.

Bill Ayers Admits He Wrote Obama's

"Dreams From My Father"

-- Just "Some Guy From the Neighborhood"??

In May 1998, Edward Said traveled from Columbia to Chicago to present the keynote address at a dinner organized by the Arab American Action Network, a group founded by Rashid and Mona Khalidi. We’ve known for some time that Barack and Michelle Obama sat next to Edward and Mariam Said at that event. (Pictures are available.) It has not been noticed, however, that a detailed report on Said’s address exists, along with an article by Said published just days before the event (Arab American News, May 22, June 12, 1998). Between those two reports, we can reconstruct at least an approximate picture of what Obama might have heard from his former professor that day.

For the most part, Said focused his article (and likely his talk as well) on harsh criticisms of Israel, which he equated with both South Africa’s apartheid state and Nazi Germany. Said’s criticisms of the Palestinian Authority also were harsh. Why, he wondered, weren’t the 50,000 security people employed by the Palestinian Authority heading up resistance to Israel’s settlement building? In his talk, Said called for large-scale marches and civilian blockades of Israeli settlement building. To prevent Palestinian workers from participating in any Israeli construction, Said also proposed the establishment of a fund that would pay these laborers not to work for Israel. Presciently, Said’s talk also called on Palestinians to orchestrate an international campaign to stigmatize Israel as an illegitimate apartheid state.

So broadly speaking, this is what Obama would have heard from his former teacher at that May 1998 encounter. Yet Obama was clearly comfortable enough with Said’s take on Israel to deepen his relationship with Khalidi and his Arab American Action Network (AAAN). We know this, because Ali Abunimah, longtime vice president of the AAAN, has told us so.

In many ways, Abunimah is the neglected key to reconstructing the story of Obama’s alliance with Khalidi and AAAN. While Abunimah’s accounts of Obama’s alliance with AAAN have long been public, they are not widely known. Nor have Abunimah’s writings been pieced together with Obama’s history of support for AAAN. Doing so creates a disturbing picture of Obama’s political convictions on the Palestinian question.

In late summer 1998, for example, a few months after Obama’s encounter with Edward Said, Abunimah and AAAN were caught up in a national controversy over the alleged blacklisting of respected terrorism expert Steve Emerson by National Public Radio. In August of that year, NPR had interviewed Emerson on air about Osama bin Laden’s terror network. According to columnist Jeff Jacoby, however, Abunimah managed to obtain a promise from NPR to ban Emerson from its airwaves, on the grounds that Emerson was an anti-Arab bigot. It took Jacoby’s research and public objections to lift the ban.

Attempting to bar an expert on Osama bin Laden’s terror network from the airwaves is not exactly a feather in AAAN’s cap. Yet Obama continued his relationship with AAAN. Abunimah himself introduced Obama at a major fundraiser for a West Bank Palestinian community center a short time later in 1999. And that, says Abunimah, was “just one example of how Barack Obama used to be very comfortable speaking up for and being associated with Palestinian rights and opposing the Israeli occupation.”

The year 2000 saw yet another public clash between Ali Abunimah and Jeff Jacoby over terrorism, along with a deepening alliance between Obama, Khalidi, Abunimah, and AAAN. In May 2000, Abunimah published a New York Times op-ed taking issue with a State Department report on the rising threat of terrorism from the Middle East and South Asia. The report focused on al-Qaeda, in particular. This was one of the most timely and accurate warnings we received in the run-up to 9/11. Yet Abunimah trashed the report. In a longer study released around the time of his op-ed, Abunimah went further, questioning Hezbollah’s designation as a terrorist organization, and suggesting that we ought to be, at the very least, “deeply skeptical” of the State Department’s warnings about Osama bin Laden.As Abunimah continued to downplay the threat from bin Laden, his ties to Obama deepened. In 2000, AAAN founder Rashid Khalidi held a fundraiser for Obama’s ultimately unsuccessful congressional campaign. Abunimah remembers that Obama “came with his wife. That’s where I had a chance to really talk to him. It was an intimate setting. He convinced me he was very aware of the issues [and] critical of U.S. bias toward Israel and lack of sensitivity to Arabs. . . . He was very supportive of U.S. pressure on Israel.” Obama’s numerous statements over the years criticizing American policy for leaning too much toward Israel were vivid in Abunimah’s memory, he says, because “these were the kind of statements I’d never heard from a U.S. politician who seemed like he was going somewhere rather than at the end of his career.” Obama’s criticism of America’s Middle East policy was sufficient to inspire Abunimah to pull out his checkbook and, for the first time, contribute to an American political campaign.

Within a year, Obama did Khalidi and Abunimah a good turn as well. From his position on the board of Chicago’s Woods Fund, Obama, along with Ayers and the other five members of the board, began to channel funds to AAAN, totaling $75,000 in grants during 2001 and 2002. Now Obama and Ayers were effectively supporting the pro-Palestinian activism of AAAN’s vice-president, Abunimah, and funding an organization founded by their mutual friends, the Khalidis, in the process.

In the first year of the Woods Fund grant, Abunimah was the focus of a critical Chicago Tribune op-ed by Gidon Remba, a former translator in the Israeli prime minister’s office. Pointing to Abunimah, among others, Remba decried attempts by “Yasser Arafat’s Arab-American cheerleaders” to “vindicate the resurgence of attacks on Israeli civilians by Palestinian gunmen and Islamic suicide bombers.” Yet Obama and Ayers re-upped AAAN’s money in 2002.

Rashid Khalidi on CNN

with Fareed ZakariaThe Terror and Crime of the

American Task Force on Palestine

An August 2002 profile of Abunimah in the Chicago Tribune quotes a supporter of Israel noting that, while he has heard Abunimah deplore terrorism, he has never heard Abunimah affirm that he “supports the continued right of Israel to exist alongside a future Palestine.” That is because Abunimah does not appear to recognize such a right. Instead, Abunimah favors a “one-state solution,” in which Israel’s identity as a Jewish state would be drowned out by an influx of Palestinian immigrants seeking the “right of return.” Abunimah’s book, One Country, which spells out his one-state solution, features an extended comparison between Israel and South African apartheid.

In the acknowledgments of Resurrecting Empire, a monograph he worked on toward the end of his time in Chicago, Khalidi credits Ayers with persuading him to write it. A core theme of Resurrecting Empire is that the problems of the Middle East largely turn on America’s failure to force Israel to resolve the Palestinian question. This claim that Israel is the true root of the Middle East’s problems is what Martin Kramer identifies, correctly, I think, as the key lesson imparted to Obama by Khalidi.

Khalidi left Chicago in 2003, after the now-famous farewell dinner at which Obama thanked Khalidi for years of beneficial intellectual exchange. The article in which the Los Angeles Times reports on that dinner adds that many of Obama’s Palestinian allies and associates are convinced that, despite his public statements in support of Israel, Obama remains far more sympathetic to the Palestinian cause then he has publicly let on.

Specifically, Abunimah has said that, in the winter of 2004, Obama commended an op-ed Abunimah had just published in the Chicago Tribune, saying, “Keep up the good work!” (This is likely the op-ed in question.) According to Abunimah, Obama then apologized for not having said more publicly about Palestine, but also said he hoped that after his race for the U.S. Senate was over he could be “more up front” about his actual views.

It didn’t turn out that way. Once Obama’s new-found stardom gave him national political prospects, he swiftly shifted into the pro-Israeli camp, to Abunimah’s great frustration. Would a reelected Obama finally be able to be “more up front” about his pro-Palestinian views, belatedly fulfilling his promise to Abunimah? In short, was Obama’s pro-Palestinian past nothing but a way of placating a hard-Left constituency whose views he never truly shared? Or is Obama’s post-2004 tilt toward Israel the real charade?

The record is clear. Obama’s heritage, his largely hidden history of leftist radicalism, and his close friendship with Rashid Khalidi, all bespeak sincerity, as Obama’s other Palestinian associates agree. This is not to mention Reverend Wright — whose rabidly anti-Israel sentiments, I show in Radical-in-Chief, Obama had to know about — or Obama’s longtime foreign-policy adviser Samantha Power, who once apparently recommended imposing a two-state solution on Israel through American military action. Decades of intimate alliances in a hard-Left world are a great deal harder to fake than a few years of speeches at AIPAC conferences.

The real Obama is the first Obama, and depending on how the next presidential election turns out, we’re going to meet him again in 2013.

— Stanley Kurtz is a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, and the author of Radical-in-Chief. via nationalreview.com

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

loading..

Featured Post

(no nuance to HillaryClinton's views) she made it clear in her recent book

IN THE MIDDLE EAST CHAPTER OF HER BOOK MS CLINTON MAKES STATEMENTS THAT AT BEST COULD BE CONSIDERED INSENSITIVE TO ISRAEL, OR AT WORST THA...

#CriticalAnalyst

-

▼

2011

(2336)

-

▼

May

(225)

- Israeli Community Forced to Build Walls to Protect...

- What distortion? NYTimes wants to accuse others of...

- picking on Mamet @NYT Magazine - Character Assasin...

- PA President Mahmoud Abbas said the Palestinian st...

- Thanks again Canada

- Israeli News: A fake Arab problem

- Egyptian General: Yes, We Did Virginity Tests, No ...

- France to vote against unilateral declaration of '...

- Hezbullah planned attack on Israeli borders with L...

- Wiener's Wiener: Dem. Rep's 'Hacking' Story Falls ...

- Carter Misrepresents Longstanding U.S. Policy, U.N...

- France 24 correspondent tortured for covering pro-...

- Attorneys from Israel and North America in a lette...

- Spain to recognize 'Palestine' on the '1967 lines'

- Iranian Ayatollah Affirms Legitimacy of Suicide Op...

- Former Mexican president Vicente Fox says Obama sh...

- Woman Takes Rapist's Penis to Police

- Israel's VC and startup industry headed for collap...

- Germany decides to abandon nuclear power by 2022

- Free Gaza Movement Response to UN: Flotilla On As ...

- Pakistanis vow to complete bin Laden's mission to ...

- Scottish "cleansed the presence of Israeli books."...

- Young Boy Gets Penis Chopped Off by Assad's Troops

- the guy who told Rabin to trust Arafat

- Cameron resigns as Jewish National Fund patron

- Steve Jones "risks political storm over Muslim 'in...

- Syria involved in UNIFIL bombing?

- Syrian rebels asked Israel for help

- The Canadian government warned its citizens agains...

- Egypt's New Buddy, Iran, Has Been Spying On Them

- Hamas declares Yassin's house declared heritage si...

- Sarah Palin rides shotgun?

- Syrians burned photos of Nasrallah (video)

- If the world supports the Arab Spring, shouldn't J...

- TIME Magazine Facilitates the Transfer of Gaza to ...

- PA police purposely fired on Joseph's Tomb worshipers

- Syria Murders Hundreds; "Pro-`Arab Spring'" West Y...

- Making Debbie Wasserman Schultz look worse

- The challenge of 2012 is to unite the Gadsden flag...

- A Great Evil Has Been Loosed Upon The World

- Nakba Historiography for EAST PRUSSIA

- Egypt permanently opens Gaza border crossing

- Hundreds of Women Report Rapes by Qaddafi Forces

- Touchy Touchy Michele Obama Bolts From Poland; lea...

- Luxury Cars Coming To Gaza!

- Turkish Scientist Could Be Jailed For Publishing R...

- Iran is Ready To Resolve a Crises... I repeat... I...

- Obama Walking a Fine Line on Borders Issue

- UNSC recommendation needed for Palestinian state

- Ali Abunimah, Edward Said, Rashid Ismail Khalidi, ...

- Young Obama Was Abused by Muslims in Indonesia

- Iran close to finalizing uranium deal with Zimbabwe

- Attorneys to Ban: Halt unilateral Palestinian stat...

- Israeli Left Says If You Oppose Obama’s ‘Peace Pla...

- U.S. meeting with the Taliban to "explore" "peace"

- The New York Times v. reality

- Looks Like Wilders is off the Hook

- Yglesias' strange definition of Jewish

- The 1967 Line

- ReAnalysis: HuffPo piece written about Islam and t...

- Erdogan's son joins IHH

- Facebook page calls for beating Saudi women drivers

- Obama wants to return Jews to Arab countries: Comp...

- Chomsky 2017: Rapture and other important dates fo...

- Largest Democratic donor won't donate to Obama

- Congress to Palestinians: Drop dead

- Obama's Toast to Queen Turns Awkward

- Nabil Shaath to IMRA - PA to hold Shalit after uni...

- BiBi to Obama: before 1967, Israel was all of nine...

- Paul Simon is Coming to Israel

- Heckler interrupts Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin...

- Femen... Remember they showed us their Boobs to fi...

- Palestinian PM suffers heart attack while attendin...

- Engineering Biological Change @NYTimes. Planting F...

- NYT: Obama "struck back" at Netanyahu

- Syria is better without Assad believes Israeli Gen...

- U.S. cable ties Saudis to Pakistan jihad

- Neturei Karta Can't Spell, Move Over AIPAC and the...

- Dreadlocks: not what comes to mind when one thinks...

- Those US stealth helicopters are so old hat

- Three Cheers for Terroristine

- Women REALLY DO SUCK: 'Bin Laden Called in His Loc...

- OMG Senator Cynthia McKinney guest on Libyan TV سي...

- Yes We Can!… Convicted Islamist Who Threatened “So...

- Aftenposten headline: "Rich Jews Threaten Obama"

- Full Text Of Obama's Speech To AIPAC

- Gene Simmons Video: Obama "Has No F***ing Idea Wha...

- Saudi Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal on Obama's handlin...

- Google abandons newspaper scanning project

- Swiss freeze funds for pro-Palestinian BADIL

- Why "1967 lines" was a gaffe - and why they are in...

- Coptic bishop warns Germany: “You are next”

- Spain: Ruling Socialist party faces prospect of "h...

- Court Filings Assert Iran Had Link to 9/11 Attacks...

- Canada won’t back Obama’s Mideast peace proposal

- Ron Paul Counters Obama Policy on Israel, Middle East

- Obama's Middle East Speech: The Opposite of Strate...

- Bering in Mind: Sex, Sleep and the Law: When Noctu...

- The Abbas-Obama Border Threatens Israel

- I don't usually believe anything the AP prints, bu...

-

▼

May

(225)