To begin with, Islamic banks are based on a corpus of doctrines called “Islamic economics,” which claims to be based on the Quran, but is actually the creation of the Islamist thinker Abu’l-A’la Mawdudi (1903-1979).

Mawdudi is both the father of Islamic economics and (together with Hassan al-Banna, founder of the Muslim Brotherhood) the father of modern political Islam. His crucial contribution to the development of Islamism has been highlighted by Seyyed Vali Reza Nasr in “Mawdudi and the Making of Islamic Revivalism,” while his role in the birth of Islamic economics has been studied by Timur Kuran in “The Genesis of Islamic Economics.”

Mawdudi, the founder in 1941 of the Islamist party, Jamaat-e-Islami, in Pakistan, was persuaded that it was necessary for Muslims to bring all aspects of life into the practice of “Islam” and submission to the will of Allah. Therefore, both the spheres of politics and economics could not be autonomous from the Quranic revelation and the Islamic tradition (sunna).

In the political field, Mawdudi asserted the need for the establishment of an Islam in which all sovereignty belongs only to Allah; thus, popular sovereignty would a usurpation of his rights. According to Mawdudi, the proclamation of faith, in which the Muslim believer affirms that “there is no God but Allah,” implies that “one should recognise no sovereign, nor accept any government, nor yet obey any law, or that one should refuse to accept the jurisdiction of any court and to carry out the command of anyone” except from Allah.

For Mawdudi, the duty of his party, the Jamaat-e-Islami, was to form an army of “Allah’s troopers,” with the goal of establishing an Islamic state where shari’a (Islamic law) could be enforced. The creation of an Islamic state was, however, just the first step: he writes, “Islam does not want to bring about this revolution in one country or a few countries. It wants to spread it to the entire world. Although it is the duty of the ‘Muslim party’ to bring this revolution first to its own nation, its ultimate goal is world revolution.”

Mawdudi, studying the French, Russian and National Socialist revolutions, was of the opinion that Islamic revolutions should have learned from them. Like Lenin, Mawdudi affirms the need for a vanguard of Allah’s army; like Trotsky, he calls for exporting the revolution worldwide.

The spread of the Islamic revolution also had to follow the example set by the Prophet Muhammad. Mawdudi affirms that:

“When every method of persuasion had failed, the Prophet took to the sword. That sword removed evil mischief, the impurities of evil and the filth of the soul. The sword did something more – it removed their blindness so that they could see the light of truth, and also cured them of their arrogance; arrogance which prevents people from accepting the truth, stiff necks and proud heads bowed with humility. As in Arabia and other countries, Islam’s expansion was so fast that within a century a quarter of the world accepted it. This conversion took place because the sword of Islam tore away the veils which had covered men’s hearts.”

To purify society from non Islamic influences (“the veils which cover our hearts”), Mawdudi also advocated the restoration of a classic tenet of Islam: the death penalty for apostasy (ridda). Mawdudi further states that such a punishment should not just be reserved for those who consciously refuse Islam, but also for all the non-practising Muslims:

“Whenever the death penalty for apostasy is enforced in a new Islamic state, then Muslims are kept within Islam’s fold. But there is a danger that a large number of hypocrites will live alongside them. They will always pose a danger of treason. My solution to the problem is this. That whenever an Islamic revolution takes place, all non-practising Muslims should, within one year, declare their turning away from Islam and get out of Muslim society. After one year all born Muslims will be considered Muslim. All Islamic laws will be enforced upon them. They will be forced to practice all the fara’id and wajibat [duties and obligations] of their religion and, if anyone then wishes to leave Islam, he will be executed.”

Advocating the necessity of emancipating knowledge from the influence of the West to give birth to a true Islamic polity, Mawdudi goes on to state: “Islam is the very antithesis of secular Western democracy.” Not only does society have to be purged from non- Islamic contaminations, but also science and knowledge. Islamic society and Islamic culture have to be pure:

“An Islamic state does not spring into being all of a sudden like a miracle: it is inevitable for its creation that in the beginning there should grow a movement having for its basis the view of life, the ideal of existence, the standard of morality and the character and spirit which is in keeping with the fundamentals of Islam. They should then, by ceaseless effort, create the same mental attitude and moral spirit among the people and on the basis of moral and intellectual tendencies so created they should build up a system of education to train and mould the masses in the Islamic pattern of life. This system would produce Muslim scientists, Muslim philosophers, Muslim historians, Muslim economists and financial experts, Muslim jurists and politicians; in short, in every branch of knowledge there should be men who have imbibed the Islamic ideology and are imbued deeply with its spirit, men who have the ability to build a complete system of thought and practical life based on Islamic principles and who have strength enough to challenge effectively the intellectual leadership of the present Godless thinkers and scientists”

Mawdudi is talking here of creating an all-encompassing Islamic ideology, able to defy Western hegemony --- an ideology able to create not just a new Islamic state and an Islamic society, but a totally new Islamic civilization, uncontaminated by what the Iranian thinker Jalal Al-e Ahmad calls “Westoxication.”

Islamization of knowledge is therefore a crucial step to carry out the Islamic revolution. But this revolution is not intended as a purely military, frontal war: it is rather a “jihadof postion, ” as in advancing from trench to trench, and described by Mawdudi as “exerting oneself to the utmost to disseminate the word of God and to make it supreme, and to remove all the impediments to Islam-through tongue or pen or sword.” All aspects of life and all realms of society are therefore seen as battlegrounds between Islam andkufr(impiety).

In this context, Timur Kuran maintains that “bringing economics within the purview of religion was central to Mawdudi’s broader goal of defining a self-contained Islamic order.” Such an approach refuses to modernize Islam, choosing instead to Islamize modernity. Muslims had to distinguish themselves from the “others”: their alimentation, their dress code, their sciences, their entire way of life had to be different from the West.

Thus, Islamic economics was born -- by the attempt of Mawdudi to give birth to a new Islamic order purged by Western influences.

Although the successive developments of Islamic economics sometimes took different directions, the birth of Islamic economics is located in Mawdudi’s attempt to create an Islamist ideology that would be alternative to the West, not one that should live with the West. The idea of a Western civilization wholly different from the Islamic is not therefore an invention of Samuel Huntington’s: Muslim intellectuals such as Mawdudi spent their entire lives arguing this thesis.

Mawdudi’s views quickly spread not just in the Indian sub-continent, but worldwide. The message of Mawdudi, for example, inspired the dictatorship of Zia ul-Haq, who ruled Pakistan from 1978 to 1988.

The leadership of Mawdudi’s movement was -- and is -- composed of intellectuals and professionals, who successfully propagated his ideas in the Muslim communities in the West.

In Western Europe, Mawdudists (under a number of different labels) currently control a vast network of mosques and associations, from the UK to Italy. Oddly, European authorities consider them as the legitimate representative of Islam. In May 2009, Queen Sonja of Norway visited the Islamic Cultural Center in Oslo, an institution controlled by Mawdudi’s Jamaat-e-Islami. A Socialist female politician, Heikki Holmås, had already paved the way in 2004, visiting this mosque during her electoral campaign. The “elective affinities” between radical Islam and the Left, explored by David Horowitz in his book “Unholy Alliance,” are among the most remarkable cultural events of the last decades. Given the friendly relationship between the Norwegian establishment and the Islamists, Mawdudi might even be a good candidate for a posthumous Peace Nobel Prize.

by Daniel Atzori

|

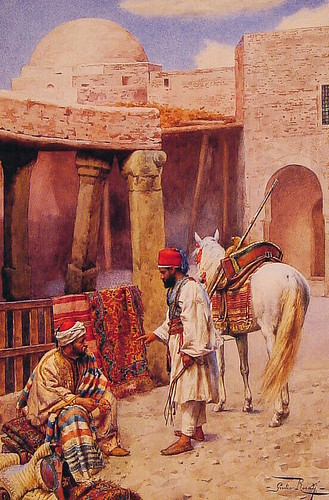

The Carpet Seller |

here is a quote from a website I found that tries to find similar ideas in Islamic finance:

The Pottery Sellers

The Carpet Seller

Ibn Khaldun is well aware of the role of supply and demand in the prices of goods in general. Unlike the falasafas and the early scholastics, he does not insist that the just price must equal labor and the cost of production. On the contrary, he argues (Ibn Khaldun II:336-337) that "commerce means the attempt to make a profit by increasing capital, through the buying of goods at a low price and selling them at a high price.... The accrued (amount) is called 'profit' (ribh)." He distinguishes this from gambling or robbery on the grounds that it "does not ... mean taking away the property of others without giving them anything in return. Therefore it is legal."

Light of the Harem

Not only is it legal, but Ibn Khaldun warns of the adverse economic effects of attempting to depress prices. Acknowledging the social desirability of low prices, especially for food staples like grain, he nonetheless warns that when "the prices of any type of goods ... remain low and the merchant cannot profit from any fluctuation of the market affecting these things, his profit and gain stop if the situation goes on for a long period. Business in his particular line (of goods) slumps, and the merchant has nothing but trouble. No (trading) will be done and the merchants lose their capital" (Ibn Khaldun II:340). He does not, however, seem to appreciate that gold and silver are also subject to market fluctuations (Ibn Khaldun II:313).

Arab Merchants It is significant that Ibn Khaldun defined profit as the value realized from labor rather than the labor itself. His frequent references to labor (literally to "activity" or "production") might deceive the unwary into believing that he is an advocate of the labor theory of value. Understanding that he talking about the profit realized from activity (including trade) takes him a step away from that school. He is aware that market value can exceed cost of production, although his understanding of why is limited to factors of place and time.I have identified two areas in which Ibn Khaldun exhibits a glimmer of understanding the subjective nature of value. The first in his assertion that gold and silver are monetary commodities because of people's (subjective) preference for their use in that capacity (Ibn Khaldun, II:231). The second is his discussion of how the prices of necessities in relation to those of luxuries indicate the strength of a civilization. Food being a necessity, the demand is always high. In a strong civilization, however, the supply is also high and therefore the price is low (Ibn Khaldun II:276). He duly notes, however, that times of natural disasters would be an exception as the supply of food would be low on those occasions (Ibn Khaldun, II:277).

Street Scene in Cairo The seeds of the quantity theory of money may be seen in Ibn Khaldun's analysis of the variations in wealth among the nations. He rejects the notion that a society is wealthy because it possesses a large quantity of monetary commodities. He notes that the Sudan has more gold than the more prosperous countries of the east. Further, he argues that the prosperous eastern nations export much merchandise. "If they possessed ready property in abundance, they would not export their merchandise in search of money...." (Ibn Khaldun, II:282). Ibn Khaldun seems to understand that a surplus of money would result in a cash outflow, and is arguing that a high level of (net) exports argues against this being the situation.If a large store of gold does not explain the wealth of nations, what does? Ibn Khaldun answers that it is because a "great surplus of products remains after the necessities of the inhabitants have been satisfied. (This surplus) provides for a population far beyond the size and extent of the (actual one), and comes back to the people as profit that they can accumulate .... Prosperity, thus, increases, and conditions become favorable. There is luxury and wealth. The tax revenues of the dynasty increases on account of business prosperity...." (Ibn Khaldun, II:281).Rothbard would have been pleased to know that Ibn Khaldun's historical research supports his view that money begins as units of weight of monetary commodities. Before the Muslims minted their own currency, they denominated the currencies available to them in the quantity their gold or silver content in weight units specified in the Islamic law (Ibn Khaldun, II:55). When the Muslims became powerful enough to do so, they melted down the old coins and issued new ones denominated in their own standard weight units (II:55-56). Since the the new coins were pure and requried no computations to determine their value, a reverse Gresham's law effect took place so that the original issues disappeared (II:60).After enough generations had passed, the Muslim officials forgot the lesson of history and "officials of the mint in the various dynasties disregarded the legal value of dinar and dirham. Their value became different in different regions. The people reverted to a theoretical knowledge of (the legal dinar and dirham), as had been the case at the beginning of Islam. The inhabitants of every region calculated the legal tarriffs in their own coinage, according to the relationship that they knew existed between the (actual) vlue of (durhams and and dinar in their coinage) and the legal value" (Ibn Khaldun II:56).CONCLUSIONSThis preliminary study provides no specific or concrete evidence of influences between the Muslim and Christian medieval scholars. On the other hand, we have found some parallels, a roughly similar level of progress, and some circumstantial evidence of links. The fact that the scholastics and the falasafas fell short of a pure free market view on the same issue--usury--and used similar arguments is provocative. Further, although the Salamanca school went beyond Ibn Khaldun, there is cause to ask whether the seeds for those advances do not lie in Ibn Khaldun's innovative approach. Additional study of scholars who lived in the period between Ibn Khaldun and the Salamancans, like al-Makrizi, remains to be done. The advanced development of economic thought in the medieval Muslim world calls out for the extension of Rothbard's study of the history of economics in Europe to the Islamic tradition as well in any case. A thorough and detailed study may or may not reveal specific links and influences. Even if it fails to produce a "smoking gun" like Russell's (1994) important discovery of Ibn Tufayl's influence on John Locke, such study would be worthwhile on its own merits.

via minaret.org

Islam is trying hard... very hard to modernize themselves. We should be wary of this. They do not seem to have any balance or reason to their theories beyond justifying their religion. When an ideology like a free market becomes brutal within itself and does not examine the exceptions to theory... we should be very skeptical. Muslims know that a purist free market would trade with Iran and other oppressive regimes.